Growing up with Friedreich’s ataxia

Being a teenager is hard enough. But growing up with a progressive disease like FA can be an education in resilience, fear, and facing the unknown.

Morgan Talevich remembers watching her older brother, Matt Lafleur, being taken to the doctor many times as a child. Then came the day when it was her turn, along with her younger sister, Mckenzie.

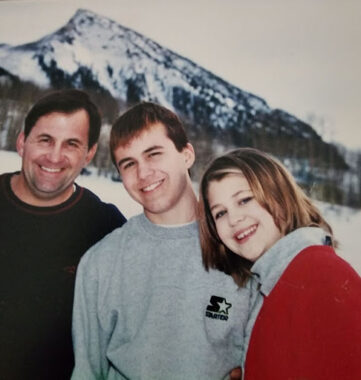

Matt Lafleur with his sister Morgan Talevich as teenagers with their dad Freddie Lafleur (Photo courtesy of Matt Lafleur)

The girls were to be tested for a genetic disease the family had never heard of before — the same one Matt had just been diagnosed with.

Morgan tested positive. Her sister didn’t. But two of the three children having Friedreich’s ataxia (FA) meant the entire family was learning how to live with a progressive condition that affects the muscles and nervous system.

Morgan describes her diagnosis as being different from other children who have it. They usually undergo testing by multiple doctors before an answer is found. She was 6 at the time and not even showing any FA symptoms.

“The only reason I was diagnosed was because my brother was diagnosed and the doctor informed my parents that it was genetic, so my sister and I were possibly candidates,” Morgan says.

Initially, the news was hard to fathom. Matt was three years older than Morgan, and both were still in elementary school. Their father, Freddie Lafleur, remembers his disbelief. “I did not know very much about FA, and there was not a lot of information available,” he says, reflecting on that fateful time in 1996.

Matt viewed the disease as an inconvenience he would soon be rid of. He decided the best course of action was to ignore it. Morgan reacted in a different way. She felt overwhelmed when the truth about her condition became clear.

“We were going to be wheelchair-ridden, we would die young, and there were no treatments,” Morgan says. “It seemed as though no one was even working on a treatment. It felt like we were forgotten and useless.”

Find an FA specialist near you

Find an FA specialist near you

Delay in diagnosis

The long road to an FA diagnosis is a shared story for children and their parents. Symptoms can start as early as age 5. A child who seems to be developing normally can start having unexplained fatigue and trouble walking.

Evaluation is based on taking a family health history, doing a physical examination, and getting genetic testing. An MRI can assess changes in the brain and spinal cord, and helps rule out other causes, such as spinocerebellar ataxia, dentatorubro-pallidoluysian atrophy, the Roussy-Levy variant of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, and cerebellar ataxia, among others.

Even though it is considered rare, FA is the most common hereditary ataxia. It accounts for roughly 50% of all ataxia cases and occurs at a rate of 1 to 40,000 people worldwide. In the U.S., the disease affects roughly 1 in 50,000 people, and mostly people of western European origin.

Right before her 11th birthday in 1998, and after going through months of testing, Laura Beth Jacquin’s FA diagnosis was confirmed. At the time, she was taking dance classes and doing gymnastics, but she was having trouble with her balance and feeling fatigued.

When her parents learned she had FA, they decided to only tell her that she had a neuromuscular disease. They wanted to wait until she was older to tell her the full truth about her diagnosis.

“I eventually learned I had FA in 2002,” says Jacquin, whose family moved from Massachusetts to Georgia so she could go to an accessible high school.

Yasin Rehmanji at home (Photo courtesy of Yasin Remanji)

Yasin Rehmanji was diagnosed with FA at age 6 on Nov. 30, 2009 — the date is stuck in his mind. He is now 20 years old and lives in the province of Ontario in Canada with his mom Sakina, dad Juzer, and brother Ali.

“At first, my parents didn’t tell me as they wanted to learn more about FA and also because they were given a different diagnosis,” says Rehmanji, adding he found out about it a year later. “They told me things as I grew up, and I also researched and asked questions along the way.”

Knowing there was a reason for what was going on with his body was a relief from the frustration of trying to do things and failing. FA became a part of his life, but it initially didn’t slow down living.

“When I was younger, I was very active and stayed busy,” he says. “I used to horseback ride, do martial arts, play wheelchair basketball, loved going on roller coasters, swimming, and sit-skiing.”

Navigating the early years

It wasn’t until 1996 that the genetic mutation that causes FA was identified. This was the same year the Lafleur siblings were diagnosed, and just two years before Jacquin’s family learned what was causing her mobility issues.

At the time, there were no medications for the condition. So the focus was on treating the symptoms, based on clinical management guidelines. (The first and only disease-modifying therapy for FA, Skyclarys (omaveloxolone), was just approved for use in February 2023.)

Having to approach treatment based on symptoms allowed Freddie Lafleur to talk to his children about FA in a way that they could understand. He would tell them how it was going to affect them, such as changes to their voice quality, loss of balance, and ability to walk.

He says he was in awe of his children’s courage and resilience, as he watched them “struggle to do simple things like write, hold a fork to eat, and transfer to and from their wheelchairs.”

Matt, who is the Bionews culture coordinator and writes a column for Friedreich’s Ataxia News, says his earliest symptoms revolved around his diminishing coordination.

“I had to let go of playing sports, and I became more and more reliant on aids in walking, such as railings on steps and walls and furniture to get by,” he says. It wasn’t until he graduated from high school that he switched to a wheelchair.

Morgan notes similar progression but says she tried to hide her symptoms when she was a teenager.

“I refused to use a walker in fear of being different from all my friends so I would always ‘sprain my ankle’ or something of the sort,” she says. “I had a very good friend of mine tell me that I must have been very clumsy because I was always on crutches, but the truth is that I liked the walk aid.”

Accepting help

It’s hard for people with chronic debilitations to show vulnerability and ask for help. They want to come across as independent and capable.

At first, Jacquin says, getting her assistance dog Munroe in 2003 gave her the independence to attend college classes, and go everywhere else.

“This was an important way for me to remain more social and involved even though my FA was progressing and limiting my mobility,” Jacquin says.

But eventually she changed her expectations about accepting help, both from people, and in the form of further mobility aids and other devices. While living in an accessible dorm at Berry College in Rome, Georgia, she hired other students to assist with Munroe and get ready for class and before bed.

“Through the college disability office, I had support for activities like note-taking and test-taking,” she says. “My friends started to help me with my hair and makeup in the mornings.”

Being able to adapt to changes in his body has also helped Rehmanji as he has gotten older. When mobility became more difficult, he started by using a Crocodile walker, transitioned to a manual TiLite wheelchair, and now has a power wheelchair with a sit-to-stand feature.

“Over the years, a lot has changed and we are constantly adapting,” he says. “I have a roll-in shower at home, with a commode for my personal care. I take many medications and they have changed over the years, too. I’m even on a trial drug right now.”

Struggling through school

Attending school with FA can be a challenge, especially when the hormonal teenage years are added to the mix.

Not every school is willing to make accommodations, is accessible for those with mobility or vision problems, or sets up an individual education plan (IEP) based on an assessment of a student’s strengths, needs, and ability to learn. Teachers may not know how to adapt set lesson plans or how to interact appropriately with a student who has a disability.

On top of that, children are quick to pick on students who aren’t like them, says Anne M. Connolly, MD , chief of the Division of Neurology at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

“Children with FA are at risk for being teased based on how they walk, how they write, and how they talk,” she says.

Matt and Morgan remember the high school years as being tough.

“School was definitely not my favorite thing. It wasn’t about academics, because that was fine,” Matt says. “But fitting in with all of my classmates was a real struggle.”

Matt has since become aware of how most people try to present themselves as strong and able. FA, he said, takes away all of those pretenses, which why he now speaks openly about his condition.

“I’ve come to learn that the people who want to converse with me may be fewer than people would suspect, but the ones who do are really meaningful,” he says. “And that is important to acknowledge.”

As the main caregivers for kids with FA, parents may find themselves acting as a shoulder to cry on, a counselor, and a cheering section. Morgan remembers leaning on her parents for support.

“One night when I was very overwhelmed by the here-today-gone-tomorrow aspect of FA, my dad told me to focus on what I can do, and not what I can’t,” Morgan says. But she says she grew into a more positive mindset. She is thankful for all the people helping her and for the research being done into finding answers about FA.

Sam Bode’s biggest challenge was the attitude people had toward him. Diagnosed at the age of 8, Bode –– who is a transgender male in his 30s –– started using a walker in seventh grade and was in a wheelchair by the next year.

The North Branford, Connecticut, resident, lives with his mother Mary and younger sister Alex, who also has FA. He says the physical barriers he encountered, like a lack of accessible bathrooms in his high school, forced him to go home when he needed to use the bathroom. And there wasn’t any way for him to wheel into his college’s cafeteria.

“Disappointingly, it was the attitudinal barriers that were the hardest to overcome,” Bode says. “For example, my junior year of high school, my guidance counselor did not sign me up for PSATs because he assumed I would not be going to college.”

And he says he is still dealing with it. “Sadly, in 2023, I still have attitudinal barriers in a society that’s supposed to be more open and accepting,” he says. “To overcome these barriers, I had my humor and friends who stuck by my side through thick and thin.”

Yasin Remanji with his brother Ali, mom Sakina and dad Juzer (Photo courtesy of Yasin Remanji)

Getting through school was also difficult for Rehmanjil. And it is still hard for him.

His slurred speech and lack of energy makes it a challenge for him to do simple things, and he tires easily. His way of coping is common to many who have to deal with fatigue and depression and other mental health problems that can lead to loneliness and isolation — not uncommon in the FA community.

“My strategy is just to avoid people and keep to myself,” he says.

Jacquin says she pushed past this by volunteering with the Muscular Dystrophy Association and the Friedreich’s Ataxia Research Alliance, and fundraising to support the development of treatments and a cure for FA. But in her mid-30s, she still struggles with social isolation and making friends.

"Over time, as the FA progressed and my vision and speech were significantly affected, it has limited my ability to have relationships with new people,” Jacquin says. “I did not have routine work experience or other activities to continue to build friendships or develop a romantic relationship.” But she does maintain close friendships with her past and current caregivers.

Passing it forward

The day-to-day tasks of dealing with FA consume a lot of energy and emotion — getting dressed, struggling with drinking a glass of water, picking up items from the floor, and accidentally running over things in a power chair. Then there’s the other everyday demands of going to school, fitting in, and graduating to life as a young adult.

Growing up with FA requires coping strategies that people living with the condition are glad to be able to pass on to younger people who are struggling with the physical and mental health aspects of living with FA.

For those who are newly diagnosed with FA, Morgan says it’s important to face the reality that this is a neurological condition. Until experimental treatments beyond Skyclarys are proven to work or a cure is found, avoiding progression of FA is a challenge.

“So use assistive devices, but don’t stop figuring out what you can still do independently,” Morgan says. “It’s something I really wish I had been told when I was younger.”

Bode recommends maintaining a respectful attitude toward others while staying hopeful that they will respect you back.

“Humor and making someone laugh, or in turn, having someone who can make you laugh. Be a good person and maybe the people around you will see that and reciprocate,” Bode says, adding, “PS: Watch out for me when I become a famous sit-down comedian.”

Rehmanji’s main advice is to stay active and try to make lots of friends. “Do not push people away,” he says. “And be physically active as much as possible even when it’s hard. Use it or lose it.”

To counter feeling isolated, lonely, or sad, Jacquin recommends staying in touch with the FA community to learn strategies for coping through the experience of others.

“Social media is a helpful way to keep up with people with and without FA,” she says. “I've learned to not be afraid to ask for help because you will be able to experience so much more in life.”

Taking care of both your physical and mental health, learning more about FA research and raising funds for research, and being gentle with yourself are other ways to manage feeling overwhelmed.

“To be young and facing FA is a real challenge. What I hope to impart is that the capability to survive, and even to strive, with this condition is attainable,” Matt says. “Even though our futures do not look as we intended, our futures matter. We matter. It’s important that nothing, especially not FA, makes us forget that.”

Friedreich’s Ataxia News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Recent Posts

- ‘Iron overload’ in mitochondria linked to heart damage in FA: Mouse study

- Getting the flu always makes my FA symptoms worse

- Yet another fall results in nose reconstruction surgery, part 2

- What it’s like on the hard days, when hope comes up short

- Skyclarys improves nerve cell function in new Friedreich’s ataxia lab study

Fact-checked by

Fact-checked by