PhD Student With FA Working on Gene Therapy for Ultra-rare Disorder

Written by |

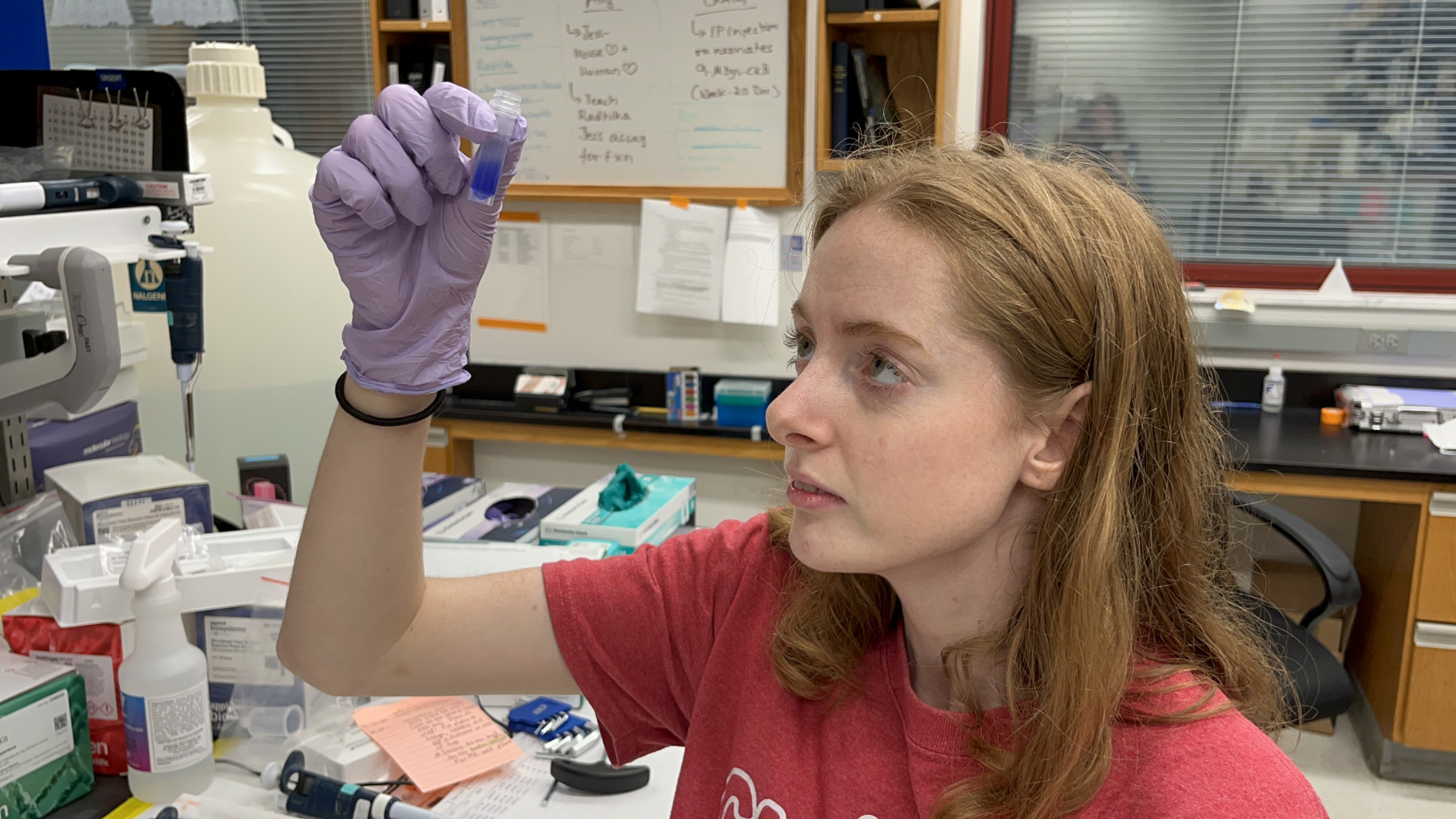

Shandra Trantham inspects a vial. (Photo courtesy of Shandra Trantham)

Shandra Trantham, 24, was a naturally inquisitive child and loved science. So when she was diagnosed with the rare neuromuscular disease Friedreich’s ataxia (FA) around age 9, she set out to learn as much as she could.

“When I had this diagnosis, and I read online that there was nothing you could do, I didn’t accept that,” Trantham said in a video interview with Friedreich’s Ataxia News. “I wanted to figure out something that I could do.”

At 13, the Jupiter, Florida native was accepted into a medical magnet high school. There, and later at the University of South Florida, she realized the best way to treat FA was at the genetic level.

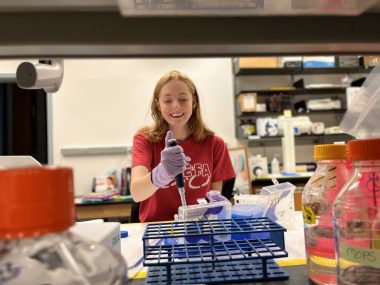

Shandra Trantham uses a pipette to work with lab samples. (Photo courtesy of Shandra Trantham)

Now, 11 years later, Trantham is working on her PhD at the Powell Gene Therapy Center at the University of Florida, known as the birthplace of using harmless adeno-associated viruses to carry genes to cells. Despite her own challenges with fatigue, balance, and walking, Trantham is working diligently to find a treatment for an ultra-rare neurodegenerative condition caused by mutations in the TECPR2 gene. Named after its gene, the disorder is known to affect just 27 patients worldwide, all of them Ashkenazi and Bukharan Jews.

“One of the things that FA patients face is fatigue, and that is something she’s able to power through. But not everyone can do that,” Barry Byrne, MD, PhD, director of the gene therapy center where Trantham works, said in a video call with Manuela Corti, PhD, associate director of the gene therapy center. “So, that’s definitely her own spirit that helps give her the motivation and drive to do that.”

Trantham works closely with other scientists who are performing an FA biomarker study (NCT02497534) of which she is a part. Corti said Tranthman adds her perspective to the work they are doing to better understand the disease. Some of her skin and muscle cells harvested for the observational study are stored in one of the lab’s refrigerators.

That study is how Trantham first connected with the Powell Gene Therapy Center nearly five years ago. But what made her want to apply to the University of Florida (UF) stemmed from the center’s work on FA gene therapy.

By the time Trantham donned her lab coat in June 2019, however, Byrne’s own biotech company, AavantiBio, which partners with UF, was already past the research phase in FA gene therapy. Byrne expects the FA clinical program to begin in late 2022.

“I quickly joined this lab, hoping that I could work on FA, but — unfortunately, as a PhD student, fortunately, as a patient — the program’s already so far along that … they’re in advanced studies for gene therapy,” Trantham said.

She’s also in the two-part, placebo-controlled Phase 2 MOXIe clinical trial (NCT02255435) for omaveloxolone, an experimental treatment being developed by Reata Pharmaceuticals to restore mitochondrial function, which is impaired in people with FA. Trial findings support the treatment’s neurological benefits and safety.

Trantham is currently running experiments on different gene therapy constructs for the TECPR2-related disorder, such as choosing varied regulatory elements to use and packing the constructs in the AAV9 viral vector. A few weeks ago, she and other researchers injected one of the constructs she created into newborn mice.

When she first joined the Powell Center, the TECPR2 project did not exist. David Ogman, whose son, Jordan, was diagnosed with the disorder, came to UF in Gainesville from Boca Raton, Florida, to meet Byrne and offer to help fund a gene therapy for the boy’s condition.

Byrne agreed and the gene therapy center received funding from the Saving Jordan Avi Ogman Foundation to develop a therapy delivered via an AAV9 viral vector. Trantham heard about the meeting while looking for a PhD project, and asked if she could join the effort. At first, she collaborated with another researcher, but now she is working solo to find a TECPR2 gene therapy.

“I know how it feels to be a patient with no treatment. While FA is very rare, TECPR2 is even rarer and there were no planned clinical trials here,” Trantham said. “I feel really lucky that I get to be able to give that hope to the patients — that someone is out there working on the disease.”

Byrne ensured that Trantham had proper accommodations to work safely in the lab. These started with the front entrance of the building, where the UF Facilities Planning and Design department replaced heavy doors that were difficult for her to open.

Because FA affects her hand coordination, a lab tech works with Trantham to carry out experiments she has designed. What might take her two hours could take the lab tech just 30 minutes. The lab also purchased a LifeGlider mobility device that provides walking support, and workers built a lab bench at a lower height to reduce the risk of her falling off a higher lab stool.

“There’s probably nothing more impactful than being day-in and day-out with someone who faces challenges in their mobility in particular, but is otherwise fully able to participate,” Byrne said.

Other researchers at first didn’t think Trantham should be given special privileges such as a personal lab tech, Byrne said. But as she began to carry her own weight in planning and executing lab work, that perception changed.

Even as she deals with FA and the painful migraines it gives her, Trantham works as hard as everyone else, Corti said, often following up with questions via text or email to “keep the ball rolling.” While a migraine might force Trantham to stay home one day, she’s there the next, Corti said.

“I have no idea how she does it,” Corti added. “I’m very impressed by the strength that she has for not giving up.”