Damage to brain’s movement pathway seen in Friedreich’s ataxia

DTT sends signals between cerebellum and motor cortex

Written by |

A brain pathway that connects the cerebellum to the motor cortex, helping coordinate and control movement by sending important signals between these two areas, is damaged in Friedreich’s ataxia (FA).

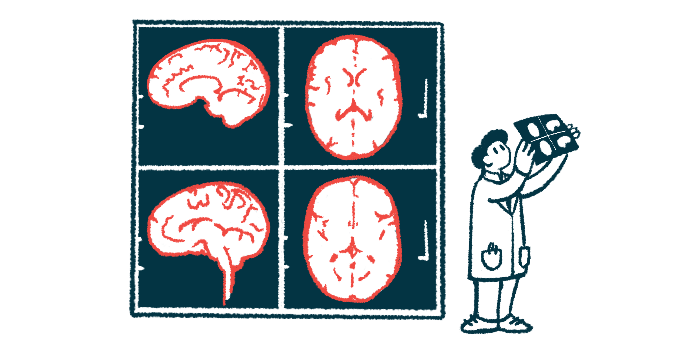

In an imaging study, researchers observed that the dentato-thalamo-cortical tract (DTT) is most damaged near the cerebellum at the back of the brain and has less damage as it gets closer to the motor cortex, just above the forehead.

“Our study further expands the current knowledge about brain involvement in [FA],” the scientists wrote in “Gradient of microstructural damage along the dentato-thalamo-cortical tract in Friedreich ataxia,” which appeared in the Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology.

In FA, muscle weakness usually results from damage to the spinal cord and cerebellum, which helps regulate timing and corrects any errors in movement, or its connections to other areas of the brain. Indeed, earlier work showed damage to the DTT, which controls voluntary movements. When this pathway is damaged, it can lead to difficulties walking and problems with coordination.

Assessing damage to brain’s motor areas in FA

Here, researchers used diffusion MRI to visualize the connections between different areas of the brain to understand better if that damage affects the entire length of the DTT equally or if some segments are more damaged than others. The study included MRI data from 45 patients with a diagnosis of FA and 37 healthy people who served as controls. Using a method called profilometry, the researchers divided the DTT into 100 small segments and then analyzed each segment using diffusion MRI, which measures how well water molecules move through the brain.

Compared to controls, the patients had lower values of a measure called fractional anisotropy, indicating damage to the myelin sheath that covers nerve fibers.

In the patients, the segments of the DTT closest to the cerebellum, particularly the one that connects a deep part of the cerebellum, called the dentate nucleus, to the thalamus, a relay station for incoming motor and sensory information, were more damaged than the segments farther along the pathway.

The findings suggest damage to the DTT starts near the cerebellum and moves toward the motor cortex. This pattern of damage moving forward is called anterograde degeneration.

To be sure the findings were specific to the DTT, the researchers also looked at the arcuate fasciculus, a brain pathway involved in language, and found it wasn’t significantly affected in FA, suggesting the DTT is particularly vulnerable to damage in this disease.

“These findings are in line with the hypothesis of an anterograde secondary degeneration arising from the dentate nuclei to the primary motor cortex, suggesting the possibility of employing [diffusion MRI] and profilometry to longitudinally evaluate damage spread and treatment response in [FA],” the researchers wrote.