Frataxin Gene Mutations Often Become Worse as Patients Age, Study Finds

Written by |

In patients with Friedreich’s ataxia, the severity of the mutation in the frataxin gene may become worse over time, according to a study published in the journal PLOS ONE.

This insight has an impact on the understanding of the timing of symptom onset, and is crucial for the development and interpretation of clinical trials, researchers behind the study said.

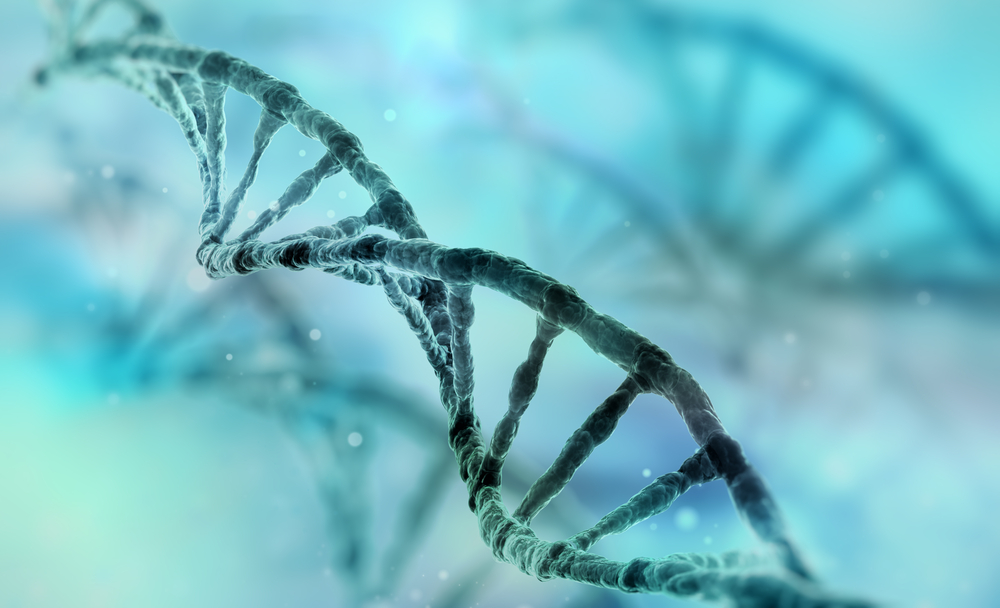

The mutation in the frataxin gene consists of repeats of three DNA building blocks — GAA. These repeat stretches prevent the protein-making machinery from producing frataxin proteins. While genes are typically stable — meaning they keep their sequence throughout a person’s lifetime — those containing abnormal repeat sequences are not.

While researchers have been aware that the GAA triplets in the frataxin gene may expand during the lifetime of a patient, there has been no systematic exploration if the gene mutation is more severe in certain tissues, or how common such expansions are.

In the study, “Somatic instability of the expanded GAA repeats in Friedreich’s ataxia,” researchers from the University of Alabama at Birmingham set out to answer a number of important questions related to this topic.

Is the GAA repeat length linked to tissue type, they asked themselves, wondering if this could explain why certain organs tend to be more commonly affected. Do these expansions get larger or smaller over time in a patient, they also asked, and do different tissues hold equal numbers of repeats?

To answer these questions, they analyzed the gene in heart, cerebral cortex, spinal cord, cerebellar cortex, and pancreatic tissues from 15 deceased Friedreich’s ataxia patients.

Just as they suspected, they found variable repeat lengths between different tissues from the same patient. Patients had on average between 428 and 914 GAAs in the five tissues analyzed. In the heart and pancreas, the gene tended to be particularly expanded with an average 752 repeats, compared to 551 to 614 repeats in the other tissues.

They also found evidence of significant genomic instability, meaning the repeats either multiplied or were cut short as cells in these tissues divided.

Since patient-derived skin cells, called fibroblasts, and blood lymphocytes are often used to study Friedreich’s ataxia, the team next compared the cell types from 16 paired samples. It turned out that lymphocytes had much more repeats that fibroblasts. The gene was more likely to expand in the blood cells.

So, to understand how such an expansion may occur over time, the team finally performed repeat analyses on lymphocytes from patients followed over time. These patients were followed over seven to nine years. In most of them, the gene expanded with time. The average expansion was a yearly increase of about four GAA repeats.

As in the other experiments, the likelihood to expand was linked to the length of the repeat, so longer repeats expanded more rapidly.

These findings may explain why symptoms appear in certain tissues and likely contribute to the speed of disease progression, researchers said.

The data also suggests that researchers should be cautious when comparing data from different tissues. Studies that particularly employ lymphocytes — often used in clinical trials — need to take into account the rate at which the gene mutation changes to generate meaningful data, they concluded.