MDA Leads in Efforts to Help Patients With Neuromuscular Diseases — From Care Centers to Research Grants and Summer Camp

Written by |

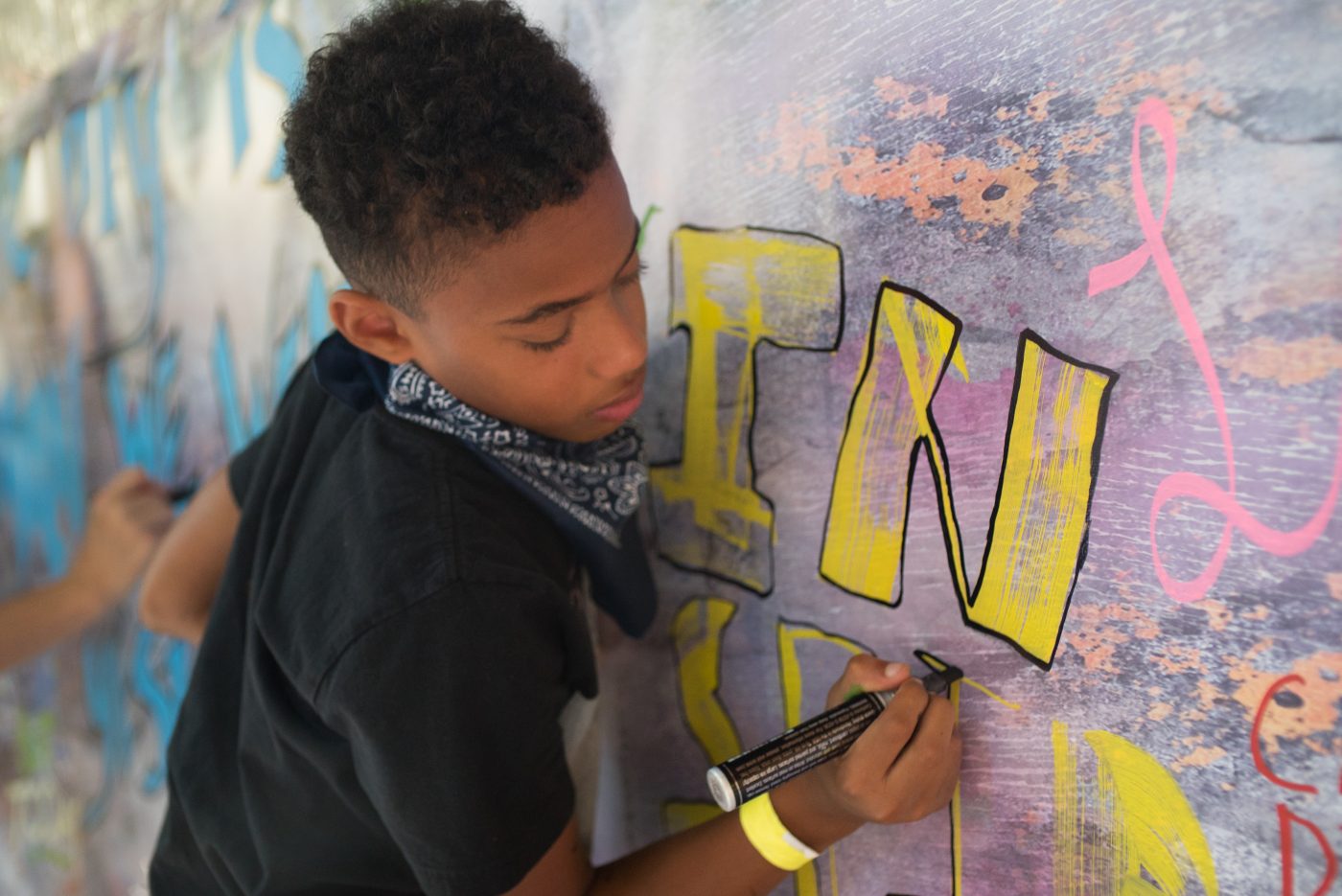

An artwork in the making at an MDA summer camp. (Photo courtesy of the MDA)

Expecting to award roughly $18 million this year in grants to support research in neuromuscular diseases, the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA) continues to be a leader in efforts to better treat and otherwise ease life for those touched by Friedreich’s ataxia as well as muscular dystrophy and other, often rare, illnesses.

That’s up from the $16.8 million in direct grants the association spent in 2019 — part of a $66-million multi-year funding commitment to the 40 distinct neuromuscular diseases it covers. Today, it reports to be the nation’s “largest source of research funding outside of the federal government.”

A number of programs stand out among those run by the nonprofit, which was started 70 years ago in the Rye, New York, office of a businessman with muscular dystrophy. These programs include:

- MDA Care Centers, which place teams specialized in neuromuscular disease diagnosis, treatment, and management in 150 clinics across the U.S.

- The MOVR Data Hub (for neuroMuscular ObserVational Research), a collection of patient data across diseases to serve both researchers and treating doctors.

- MDA Summer Camp, a chance for young people to enjoy their independence and the outdoors at a camp staffed by health professionals and trained volunteers. Most are now accepting applications for this year’s program.

These programs bring a lot of value to patients and to the scientists and doctors working to make their lives a bit better, said Sharon Hesterlee, PhD, an executive vice president and chief research officer for the MDA, in an interview with Bionews Services, the parent company of this website.

“To have this support network built-in is a great service,” she added.

Care centers and data gathering

The MDA network of neuromuscular specialist care centers runs out of more than 150 clinics across the U.S., with at least one in each state. On average, about 55,000 individual visits are made to a center each year.

Each center is staffed by a team of specialists in these diseases, working with patients from diagnosis through to treatment management.

“They network and offer top-notch care,” Hesterlee said, “and they’re all aware of therapy development.”

Anyone who suspects that they or a family member or friend may have a neuromuscular disease can get help in finding a nearby clinic through the MDA Resource Center, or by using the search tool provided on the MDA’s dedicated webpage.

This network is supported by the MDA, which helps offset the cost of services to the people using them, Hesterlee said.

Research is also conducted at these centers, with many being major clinical trial sites, including Boston Children’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Massachusetts, and Nemours Children’s Hospital and the Mayo Clinic in Florida.

Collecting information about patients and their disorders, of use in both research and care, was a natural next step.

“We have long-standing relationships with the centers and their directors and staff,” Hesterlee said. “It was sort of a no-brainer to set up a database and start collecting data at the point of care in the diseases that we cover.”

The effort actually began in 2016, but a decision was made to transition to a more sophisticated platform about a year ago.

The result is the MOVR Data Hub, jointly operated by the MDA and the contract research organization IQVIA.

Data capturing disease, diagnostic, and encounter information over time, collected by clinicians and self-reported by patients, is being fed into MOVR, adding to the “legacy data” gained over the previous three or so years, Hesterlee said.

To date, seven neuromuscular diseases — amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, Becker muscular dystrophy, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, and Pompe disease — are included, covering about 4,000 people.

Expansion into the 33 other diseases under the MDA umbrella is planned, with about 40 care centers already approved to take part and another 40 working through the process.

Patients or treating clinicians can request to participate in MOVR, but signed consent is required and patient data carefully protected. It’s “highly curated, very high quality data with good quality assurance,” and compliant with federal regulations necessary for regulatory filings, Hesterlee said.

“We would like to see every patient seen at an MDA site with a platform have the opportunity to participate,” said Kristin Stephenson, chief of advocacy and care services, and an executive vice president with the MDA.

Potential uses of this information by doctors and researchers, Hesterlee said, range from comparing patient responses and outcomes across clinical centers, to helping investigators with questions about endpoints or progression in a rare disease.

“Industry is certainly interested in using the data for feasibility studies for clinical trials — like establishing eligibility criteria — and a potential interesting use is as a comparator for a placebo arm” in a study in patients.

“In rapidly progressing, serious diseases, it’s really hard to have a placebo group,” she added.

Stephenson said that each of these diseases “are rare diseases by definition, and some very, very rare in terms of the total population living with the disease. So, the reality is that you can have a smaller cohort that can still yield very meaningful data.”

For kids, there’s summer camp

Each year at no cost to families, the MDA welcomes children ages 8 to 17 to take part in its week-long summer camp program, “where kids with muscular dystrophy and related diseases can live beyond [their] limits.”

The camps, run at 53 sites in 34 states, are staffed by health professionals — including those at its care centers — and

trained volunteers. Children can enjoy activities ranging from sports and games to arts and crafts, with counselors to help with activities and personal care.

“The kids say it’s the best week of their year. The parents find it wonderful,” Hesterlee said. “When you have a medically fragile child, it’s hard to be able to leave them, yet [parents] desperately need that break. … knowing that we have the same level of staff that’s in the clinic at the camp — it gives them the comfort they need.”

A new addition to camp life is teaching kids to problem-solve like a firefighter, a program suggested by firefighters themselves when invited by the MDA to expand on their traditional daylong visits to the camps.

“Firefighters used to just show up and do a fun camp day and bring fire engines, which the kids love,” Hesterlee said, adding that problem-solving is an equal — and highly practical — hit.

“They think it’s fascinating,” she added. “When you’re living with any of these diseases, you have a lot of problem-solving to do.”