Juvenile-onset Friedreich’s Ataxia Patients Have Abnormal Structures Linked to Heart Disease

Written by |

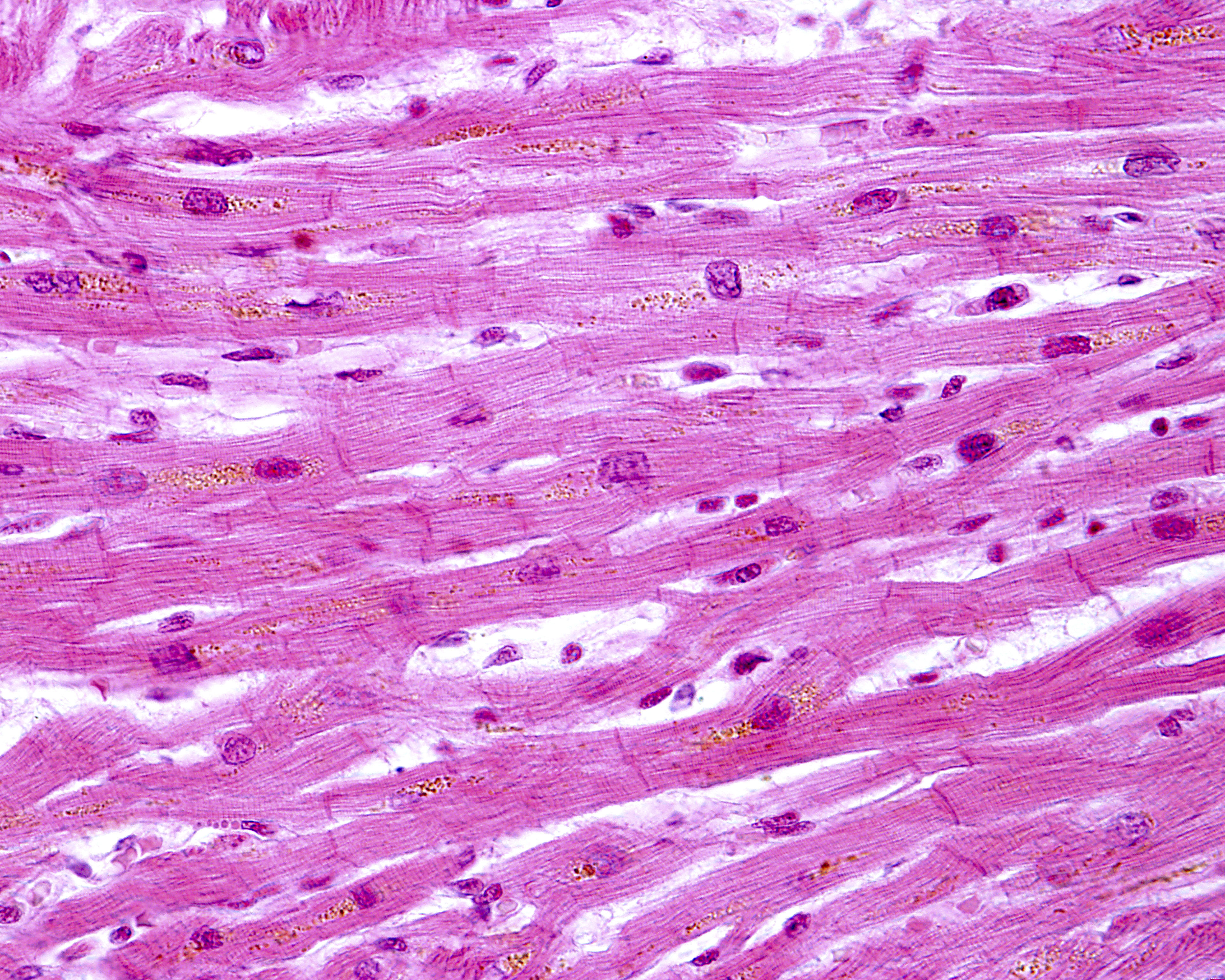

Younger Friedreich’s ataxia patients have an abnormal assembly of heart structures called intercalated discs (ICD) which prevent proper transmission of signals between heart muscle cells and contribute to heart disease.

The study, “The significance of intercalated discs in the pathogenesis of Friedreich cardiomyopathy,” published in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences, suggests that frataxin replacement therapy could possibly mend the structures to re-establish sufficient communication and connections between heart muscle cells.

Cardiomyopathy, or diseased heart muscles, is the most frequent cause of death in Friedreich’s ataxia patients. This abnormality, as well as those seen in skeletal muscle, is caused by the lack of frataxin, and researchers have studied the anatomic, cellular, and molecular changes in great detail.

But one structure — the intercalated disc — has received relatively little attention. Intercalated discs connect individual heart muscle cells with each other, so that when a signal to contract reaches one cell, it rapidly spreads, allowing all the cells to contract in a synchronized fashion. The discs hold molecular structures that allow ions to pass while tightly connecting the cells.

To take a closer look at the role intercalated discs may play in Friedreich’s ataxia heart disease, researchers at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Albany and Albany Medical College in New York analyzed heart tissue from 18 deceased patients and 12 controls that had died of unrelated causes.

The age at death ranged from 10 to 87 years for patients and similar ages in controls.

Researchers found that in patients with juvenile-onset Friedreich’s ataxia, the intercalated discs were larger than normal and had an irregular appearance. Instead of the normal shape of a slightly curved line, analyses showed discs that had a more zig-zag-like appearance, with some discs not fully formed and others duplicated.

Proteins making up desmosomes and gap junctions — the molecular complexes keeping cells attached and communicating — were also abnormally distributed. One of the proteins was commonly found in the plasma membrane lining the cells in addition to the irregular presence in the intercalated disc.

In contrast, two patients with late-disease onset who survived for a long time had neither heart disease nor an abnormal appearance of the intercalated discs.

“The specific mechanism by which frataxin deficiency causes the mismatch of ICD and hypertrophic heart fibers in [Friedreich’s ataxia] is unknown,” the authors wrote. “Frataxin replacement therapy may re-establish sufficient communication across gap junctions and restore normal end-to-end mechanical adhesion of heart fibers.”