Glial Satellite Cells in Friedreich’s Ataxia Are Independently Affected by Disease, According to Researchers

Although Friedreich’s ataxia is mainly associated with the degeneration of neurons, a recent report shows that glial satellite cells in the spinal cord are also affected by the frataxin gene mutation. This appears to be a process independent of neuronal cell death, and likely contributes to disease manifestations in Friedreich’s ataxia — a finding that advances our understanding of this devastating disease.

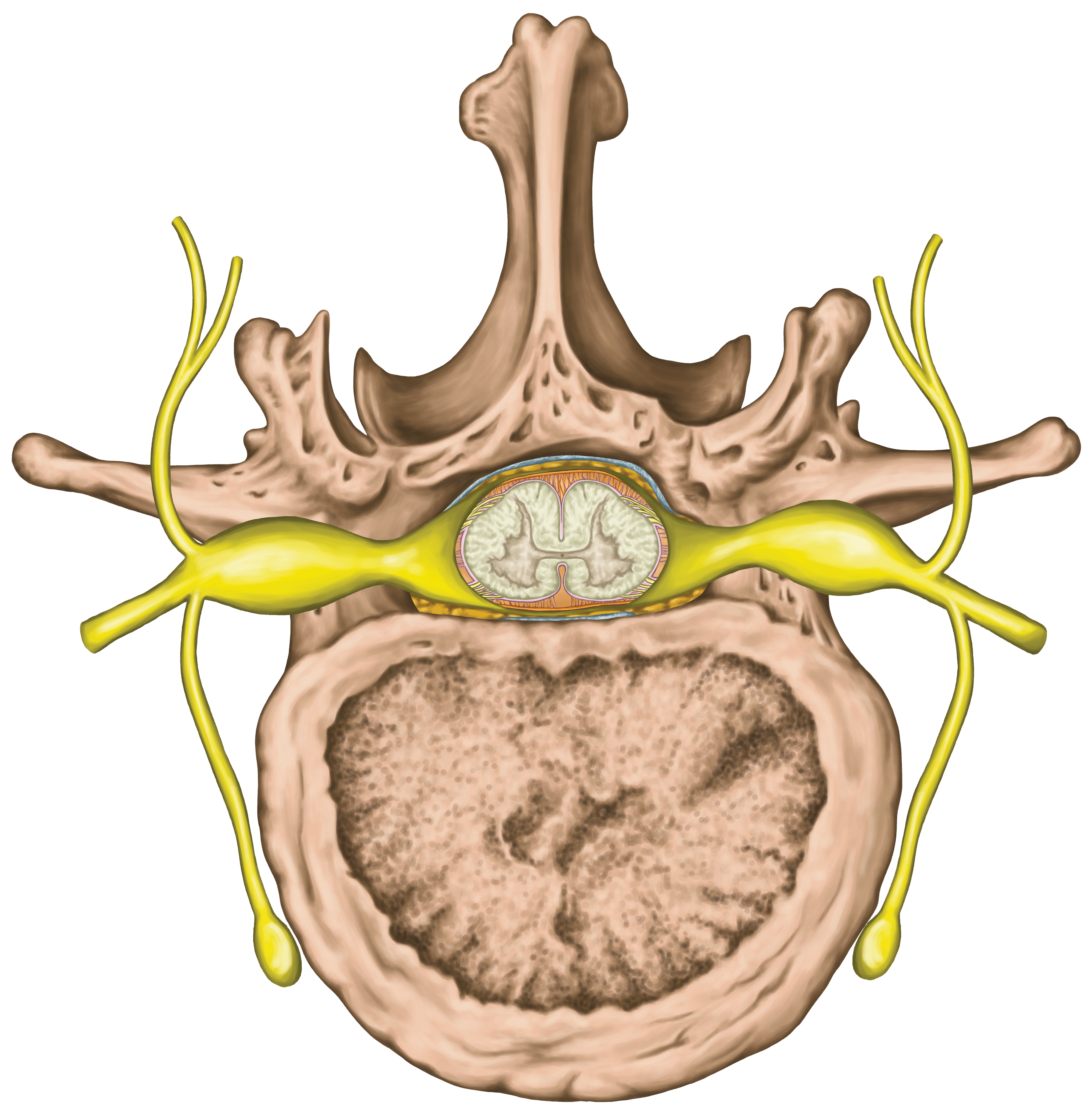

Glial satellite cells cover neuronal cell bodies in ganglia — nerve cell clusters of the autonomic nervous system, controlling bodily functions that we cannot control. A ganglion collects neurons sharing the same function or cover a particular body region. Dorsal root ganglia — present in the back part of the spinal cord — contains cell bodies of sensory neurons.

While death of dorsal root ganglia neurons is a hallmark of Friedreich’s ataxia, scientists have not focused on accessory cells to the same degree. Research during the last decade has shown that accessory cells such as satellite cells or astrocytes actively modify nerve cell signaling. A deficit in satellite cells could therefore contribute to disease manifestations.

The research team at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Albany, New York, together with colleagues at Albany Medical College used tissue from 15 Friedreich’s ataxia patients and 12 healthy control individuals to study how mutations in the frataxin gene affected dorsal root ganglia satellite cells.

Results, published in Acta Neuropathologica Communications, demonstrated the evidence of a substantial impact in satellite cells by frataxin gene mutations. Satellite cell layers were disrupted and reorganized into thick sheets, instead of the thin layers present in healthy people. In contrast to dying neurons, these supportive cells were multiplying more than in healthy people, also spreading their processes to neighboring cells.

The satellite cells also had more connections with each other, indicating a higher level of communication between cells, and had more mitochondria, with higher levels of frataxin, than the neurons they were encircling. This finding suggests that a frataxin deficiency does not impact the production of mitochondria per se, but more studies are needed to explore whether the satellite cells mitochondria are normal, or if they show more subtle signs of dysfunction.

Levels of other molecules crucial for normal cell function were disturbed, and the study, titled “Dorsal root ganglia in Friedreich ataxia: satellite cell proliferation and inflammation,” also found evidence of iron leaking from dying neurons, which led to an increased iron storage in the surrounding satellite cells.

In addition, the research team noted high numbers of immune cells, called monocytes, in the ganglions, penetrating the satellite cell layers, and at times also nerve cell membranes, showing that the disease processes were linked to a high level of inflammation.