Iron-binding Molecules Could Protect FA Patients from UVA Damage to Cells, Study Suggests

Written by |

Adding a molecule that specifically binds iron in mitochondria to sun creams could help protect the skin cells of Friedreich’s ataxia (FA) patients from their increased sensitivity to damage caused by ultraviolet A (UVA) radiation.

Besides FA patients, this discovery might benefit people living with other disorders also characterized by iron overload in mitochondria, such as Wolfram syndrome and Parkinson’s disease, the researchers suggested.

The study with these findings, “The role of mitochondrial labile iron in Friedreich’s ataxia skin fibroblasts sensitivity to ultraviolet A,” was published in the journal Metallomics.

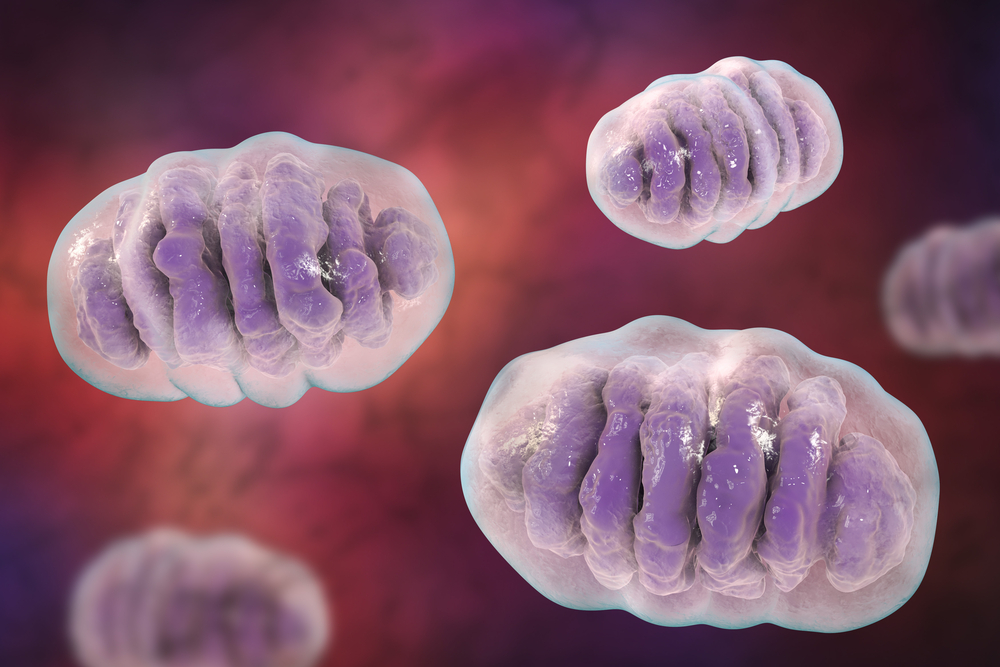

Iron, in its labile (easy-to-change) form, is implicated in the formation of harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS) — free radicals that may damage DNA, lipids (fat) and proteins. Most labile iron within the cells is found in mitochondria (the cell’s power plants), which makes these organelles the source of most ROS and particularly susceptible to oxidative stress.

Prior studies showed that mitochondria of skin fibroblasts (connective tissue cells) are a major target of damage induced by UVA radiation, which leads to cell death.

The deficient levels of the protein frataxin in FA ultimately result in mitochondrial iron overload, dysfunction, and accumulating oxidative damage. Research in cells from FA patients and in a mouse model of the disease suggested that iron chelators (which trap or remove heavy metal ions) lessen oxidative damage and ease cardiac symptoms. However, their insufficient specificity means better options are needed.

Connect with other people and share tips on how to manage FA in our forums!

To address this gap, the team at University of Bath, King’s College London and Brunel University London had developed iron chelators, molecules highly specific to iron, bound to a mitochondria-specific peptide. In vitro experiments showed these molecules protected skin fibroblasts from solar UVA-induced damage.

The researchers now found that skin fibroblasts from people with FA are up to 10 times more susceptible to UVA damage than those from healthy controls.

“Our results – should they translate to people’s skin (in vivo), suggest that patients could be up to 10 times more sensitive to UVA. The damage you and I would get in our skin from for example 2.5 hours’ exposure to solar UVA would be 4-10 times higher for a patient with [FA],” Charareh Pourzand, the study’s senior author, said in a press release.

The greater risk in FA cells correlated with approximately 6.5-fold higher levels of labile iron in mitochondria, which then contributed to increased ROS generation upon exposure to UVA.

“There’s a vicious cycle,” Pourzand said, “excess iron in the mitochondria means more reactive [oxidizing] species and more damage to cell constituents, resulting in cell functions being compromised.”

Then, the team found that pre-treatment of fibroblasts with an iron chelator specific to mitochondria suppressed the production of free radicals, prevented cell death, and reduced in half both the damage to the mitochondrial membrane — a measure of mitochondrial function — and the depletion in ATP (the molecular currency of energy).

Similar results, although to a lesser extent, were observed in fibroblasts derived from a mouse model of FA with low levels of frataxin.

The team ultimately aims to boost the protective effects of sun creams against UVA rays. “Our research shows that adding an iron chelator to sun creams could enhance the photoprotective capability of current preparations and be particularly beneficial to people with acute sensitivity to solar UVA,” Pourzand said.

Overall, the findings also suggest that “skin fibroblasts which can readily be obtained from [FA] patients could be used as a predictive tool to determine their sensitivity to UVA,” the researchers wrote.