Experts Barry Byrne, Jerry Mendell Lead NORD Webinar on Gene Therapy

Written by |

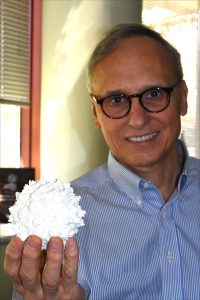

Barry Byrne, MD, director of the UF Powell Gene Therapy Center in Gainesville, addresses PPMD’s June 2019 conference in Orlando. (Photo by Larry Luxner)

A glance around the walls of Barry J. Byrne’s office reveals a lot about the pediatric cardiologist who runs the Powell Gene Therapy Center at University of Florida (UF).

In one corner is an unusual painting by 9-year-old Will Barkowsky of Jacksonville, Fla. Will, the first boy with Duchenne muscular dystrophy to take Sarepta Therapeutics‘ exon-skipping medication Exondys 51 (eteplirsen), put together his oil-on-canvas masterpiece using the tire tracks of his wheelchair, making sure the colors didn’t mix.

Nearby is a movie poster for “The Ataxian” — an award-winning 2015 documentary by Kevin Schlanser and Zack Bennett about 17-year-old Kyle Bryant, who despite having Friedreich’s ataxia embarks on a cross-country bicycle trip with three buddies.

Another movie poster advertises “Extraordinary Measures,” the 2010 tearjerker starring Brendan Fraser as John Crowley — the father of two kids with Pompe disease and later, the founder of Amicus Therapeutics — and Harrison Ford as fictional researcher Robert Stonehill, who discovers a treatment for the genetic disorder that eventually saves the lives of Crowley’s children.

There’s also a model of a Blalock-Taussig shunt frequently used in congenital heart surgery, as well as one of an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector, along with a prominent photo of Byrne with Ron Bartek, co-founder and director of the Friedreich’s Ataxia Research Alliance (FARA).

“Friedreich’s ataxia is where we’re putting most of our efforts now,” said Byrne, who spoke to Bionews Services — publisher of this website — at length during a recent visit to his lab in Gainesville, Fla.

Byrne, along with Jerry Mendell, MD, a neurologist with Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, hosted a Nov. 20 webinar on gene therapy organized by the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) and the American Society for Gene & Cell Therapy.

The two experts were introduced by Katie Kowalski, senior program manager for NORD’s Educational Initiatives. The webinar, “Understanding the Gene Therapy Process and Aftercare,” was the fourth in a five-part series underwritten by Amicus and Sarepta, as well as two other companies, Avrobio and Bluebird Bio.

The final webinar in the series, “Life After Gene Therapy,” is scheduled for Dec. 18.

Getting mutations, antibodies right

Mendell, who heads Nationwide’s Center for Gene Therapy, specializes in gene therapy research for Duchenne as well as limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and X-linked myotubular myopathy. He was a principal investigator for the Novartis therapy Zolgensma, which uses an AAV vector to carry a working version of SMN1, the mutated gene in people with SMA.

Zolgensma won approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in May 2019 as the first gene therapy to treat SMA in infants up to 2 years of age.

At $2.125 million per patient, the hour-long Zolgensma infusion is the most expensive medicine in history. The cost easily eclipses that of the only other FDA-approved treatment for SMA, Biogen’s Spinraza (nusinersen), which retails for $750,000 the first year and $375,000 every year after.

“Many of my colleagues have been trying to make inroads for years,” Mendell said. “When we first got into the gene therapy domain, we were limited by technology. We could not make enough virus for the kind of impact we’re having now. But technology has improved, and we can now deliver genes through circulation to reach all muscles.”

Regardless of the disease, he said, it’s extremely important to confirm the patient’s specific mutation before anything else.

“This is critical, because you don’t want to deliver the wrong kind of gene in a disease like Friedreich’s ataxia. That goes for all gene therapy trials,” he said. “Next, we want to check for pre-existing antibodies, whether they’re acquired from the environment or from close contact. They bind to the AAV and block entry to the target organ.”

Checking for those antibodies requires a blood test. It generally takes 4-7 days to return lab results — a “nailbiting time” for patients and families, Mendell said, “because they’re waiting to be approved for enrollment in the trial.”

Byrne estimated that 50-60% of all individuals may have been exposed to AAV.

“Prior exposure at any level to any AAV infection is an exclusion in most studies,” he said, noting that people who travel frequently or who have respiratory or gastrointestinal conditions are particularly susceptible. “We are learning a lot about what thresholds are effective. It’s about 10% of newborns and about 50% of those of school age and adulthood.”

Patients must also be in general good health — except, of course, for the genetic disease being treated. MRI and blood tests are done to rule out diabetes or any evidence of heart, liver, or kidney problems.

“We put the patient to sleep so there’s really no pain involved,” Mendell said. “We also use local numbing medicine, even though the patient is asleep, so there’s no pain or discomfort.”

How durable is gene therapy?

The Powell Gene Therapy Center was established in 1996 — the year before Byrne joined UF — by Nicholas Muzyczka, PhD, who performed groundbreaking work on AAVs in the 1980s. The center has a dozen individual labs working in neuroscience and molecular genetics.

Byrne said that because gene therapy fundamentally changes many of the body’s cells, screening is crucial.

“This is often a one-way street, in that since the effects are long-lasting, other experimental studies may not accept patients who have received gene therapy of any kind in the past,” Byrne said. “One must have the clinical features required of the study and meet certain functional and age criteria.”

To prepare for screening, patients or their parents must read the informed consent and understand what the risks and benefits are. Genetic counseling also may be required to determine whether a given mutation is amenable to gene therapy.

“Baseline evaluations are done when it’s a muscular skeletal disease — timed function tests as well as lab tests — and a study schedule is established,” he said. “In many of our studies, we see the patients very frequently, almost every day for the first two weeks. They stay in the area for up to a month. Because we’re often dealing with rare populations, that makes it convenient for us to evaluate these patients.”

Byrne noted that gene therapy is not necessarily durable for the lifespan of the patient. Because the delivered gene does not integrate into the cells’ own DNA, it is not passed down to newly formed cells.

“Some cells, particularly in the liver and muscle, continue to grow throughout childhood and AAV doesn’t integrate, so it’s progressively less effective — unless the cells being targeted, as in SMA, are not dividing,” he said. “That’s an example where newborn screening is critically important to better outcomes.”

Mendell said he generally starts patients on prednisone one day before receiving gene therapy in order to suppress liver inflammation, and keeps them on it for 60 days after.

“When we’re in the room, the first thing that happens is the gene is delivered. You push a button and get started,” he said. “Obviously it must be the correct gene. It’s in there, but you can’t see it.”

After the infusion, what next?

The actual gene is delivered by intravenous (IV) infusion with a pump over a 90-minute period, Mendell said; anything faster than that could potentially cause harmful side effects.

“We put IVs in both arms for continuous delivery in case one side gets clogged up. We don’t want anything to stop gene delivery,” he said. Meanwhile, the patient is constantly monitored for vital signs. “We invite the whole family to stay together, and that’s reassuring. There’s anxiety about gene therapy, but the potential benefits generally outweigh any risks involved.”

Some patients may develop nausea and vomiting in the first one-to-three weeks following treatment. For this reason, blood is taken every two weeks for three months to check for side effects.

Mendell said he knows patients are responding to gene therapy by doing testing. In the case of Duchenne, he uses the North Star Ambulatory Assessment, which includes 17 timed tests such as climbing stairs, rising from a sitting position, and walking or running 100 meters. In addition, neck control is a very good indicator of efficacy among Duchenne boys, he said.

The FDA anticipates that within the next 10 years, it will approve up to 40 gene therapies for rare conditions. Mendell said the benefits of gene therapy for one condition in particular, SMA, are undeniable.

“This is an absolutely devastating disease. In type 1 SMA, patients usually don’t survive past age 2, and about 50% are gone by age 1,” he said. “Initially there was concern about giving this to infants, but we told the FDA we needed to test infants in order to save lives.”

Continuing results from Mendell’s pivotal Phase 1 trial (NCT02122952) in 15 type 1 infants and a long-term extension study (NCT03421977) have changed the way people view gene therapy’s potential in general.

After four years, he said, “every patient in our trial went from being unable to sit to being able to, and several are able to walk. One patient was treated 28 days after birth, and now four years later, he’s off to school. What Barry and I do is very gratifying, and we thank our patients and their families for this opportunity.”