#IARC2017 – From a Son’s Plea for Help, GoFAR Grew to Become Leading Light of FA Community

Filomena D’Agostino will never forget Christmas 2002.

That was the day her 20-year-old son, Diego, tears streaming down his face, begged her and her husband Bernardo Ruggeri to do something to improve his Friedreich’s ataxia.

That fervent plea from their son — who developed the disease at age 6 — prompted the couple from Torino, Italy, to establish the nonprofit organization RUggeri DIego to promote research on the neurodegenerative condition.

As word spread about what the couple were doing, FA communities in Italy and other European countries asked them to expand the program. Some two years later, in 2005, they founded GoFAR, which stands for Go Friedreich’s Ataxia Research, D’Agostino said in an interview with Friedreich’s Ataxia News.

In the 12 years since, GoFAR has become such an important force in the global quest to find a cure for FA that it will host next week’s Second International Ataxia Research Conference, IARC 2017, in Pisa, Italy.

The Sept. 27-30 gathering is the world’s largest ataxia convention. In addition to GoFAR, its main organizers are the Friedreich’s Ataxia Research Alliance (FARA) of the United States and Ataxia UK.

One of GoFAR’s first initiatives — begun in 2006 — was to encourage FA organizations worldwide to work together on advancing research into a disease so complex that experts say it is too difficult for any one nonprofit to handle. It succeeded in persuading organizations in several countries to meet for the first time, kick-starting the global collaboration movement.

People with an ataxia can have a multitude of symptoms, including movement difficulties, vision and hearing loss, and heart dysfunction. The disease usually appears in adolescence or early adulthood.

“Our aim has been to create a great alliance between people affected by FA and the various patients’ organizations around the world to identify and jointly support economically the most promising studies aimed at identifying an effective treatment,” D’Agostino said.

The collaboration will be on display at the Pisa conference, said Jennifer Farmer, FARA’s executive director, adding that there’s no better way of “pulling the scientific community together” on the ataxia challenge than a conference like IARC.

The convention will cover many of the 100 or so ataxias, not just Friedreich’s. Most are inherited rather than a result of head trauma or other environmental causes, so many presentations will be on the inherited forms of the disease. FA is the most common inherited ataxia, and it will receive considerable attention at the convention.

One of the saddest features of an inherited ataxia is that it can strike a family more than once, increasing the burden of care as well as the cost.

This happened with D’Agostino and Ruggeri. Their daughter, Alice, was born in 1986 and developed FA at the age of 18. Now 31, she has two children — a 2-year-old son and 4-month-old daughter.

“Our motivation is our children, the children of those who support us, and all people affected by FA around the world,” D’Agostino said. “The support of other families with FA gives us the strength and vigor to continue the difficult and sometimes frustrating work we do — in hopes of offering them a better life.”

GoFAR chose the historic city of Pisa, home of the famed Leaning Tower, as the IARC convention site for a couple of reasons.

First, the University of Pisa, which is hosting the conference, was founded in 1343 by Pope Clement VI. It is one of the world’s oldest and most renowned centers of learning. Second, its rector, Paolo Maria Mancarella, has been a longtime champion of the disabled, D’Agostino said.

Mancarella is former president of the National University Conference for the Disabled, an effort to better integrate people with disabilities into university life.

“GoFAR is particularly proud that Professor Mancarella has accepted our invitation to address the IARC participants, because he cares a great deal about the problems of the disabled,” D’Agostino said.

One of the most popular features of the first IARC convention at Windsor, England, in 2015, was ataxia patients’ addresses to participants. Their riveting accounts of the daily challenges they face and what they would like to see research accomplish inspired the scientists there, according to conference organizers.

A highlight of the Pisa convention will be a roundtable at which five patients and caregivers talk about what they would like to see clinical trials of ataxia therapies cover. The hope is for researchers to use their ideas to design trials that assess what patients most want treatments to accomplish.

D’Agostino said two of the five panelists will be Matteo Varbaro and Filippo Fortuna — both Italians with FA.

The IARC conference in Windsor generated a lot of buzz because it was the first ataxia convention of its size and scope. The Pisa conference is creating excitement because of promising new treatment developments. They include gene therapy, gene editing, and efforts to adopt approved treatments for other neurodegenerative diseases to ataxia.

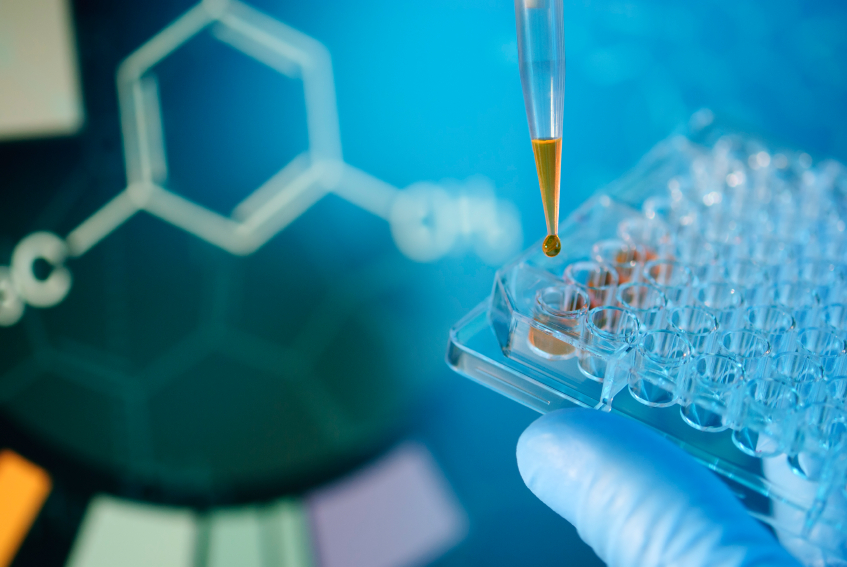

GoFAR is particularly interested in presentations dealing with “the development of epigenetic drugs, and gene replacement approaches to restore frataxin levels in Friedreich’s ataxia patients,” D’Agostino said.

Epigenetic therapies focus on processes that direct genes to turn on or off, what is known as gene expression. “While the cell’s DNA provides the instructional manual [for the way genes should work], genes also need specific instructions,” according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, a unit of the National Institutes of Health. “In essence, epigenetic processes tell the cell to read specific pages of the instruction manual at distinct times.”

Faulty genes’ inability to produce the frataxin protein is the cause of FA, scientists say. Gene therapy encompasses a number of approaches, like gene replacement therapy, which replaces the defective gene to create a normal and functional version of frataxin. The normal genes should be able to produce the protein that the faulty ones cannot, scientists say.

Funding for ataxia research comes from a number of sources, including governments, universities, foundations and nonprofit organizations like GoFAR whose main objective is promoting ataxia research and care.

All three of the Pisa conference organizers — GoFAR, FARA and Ataxia UK —are funding research projects that scientists will present at the convention.

An important GoFAR-funded project is a $750,000 University of Florida gene therapy development effort. Drs. Barry Byrne and Manuela Corti will be sharing with conference participants the results their Florida team has achieved so far.

A glance at the convention program shows a lot of Italian names among the scientists who will be making presentations — some working in Italy but many working elsewhere.

Italy has been a bastion of medical and biological research for centuries, D’Agostino said. It has been particularly strong in rare disease research over the past half century, experts say. This has prompted a number of rare-disease research facilities in other countries to hire Italians — including ataxia experts — in their programs.

In addition to the new therapy approaches that the Pisa conference will spotlight, another sign that momentum in ataxia research is building is an increase in the number of pharmaceutical companies at the gathering. About 24 such companies are likely to participate this year, up from 14 to 16 at the initial IRAC convention in Windsor two years ago, organizers say. Altogether, about 350 conference participants are expected.

Like the new therapy approaches, the increase in corporate interest is helping those in the FA community — like GoFAR founders Filomena D’Agostino and Bernardo Ruggeri — cautiously raise their hopes that meaningful treatments for the disease are coming.